A recent Facebook post looked at a published JLA cover by Neal Adams and an unpublished but surviving earlier version by Gil Kane, noting that the changes from one to the other were comparatively minor. The poster (David Seidman, a good soul) wondered why.

I have no inside information on that particular incident, but it made me think it was worth talking about the broader subject of Carmine and covers. In the era of newsstand sales being the dominant model for comics in America (let’s say roughly 1935-1984?), the conventional wisdom was that the cover was by far the most important element in an issue’s success. Different theories were built around this (e.g., change the logo’s color and the dominant background every issue so potential customers would notice subliminal it was a new release, or put a talking gorilla prominently in place). Certainly the principal character mattered, and Steve Ditko’s innovation of the Marvel ‘corner box’ was a way of making sure that even in racks that hid the bottom two-thirds of an issue, the character was still up there as bait. But if it was a very popular character, they might be on multiple covers at the same time (remember when there were over 20 Richie Rich titles?), so the specific cover still mattered, maybe as much or more than the starring persona. That was, of course, the logic Carmine was brought up in, and in part, his ticket to the top.

Carmine was pretty much inarguably DC’s star artist in the mid-60s when he was promoted to supervise or design most of the company’s covers. DC’s best sellers were still far outselling pretty much everything on the newsstand. It’s likely that the issue of LOIS LANE with Superman yanking off his Clark Kent glasses and insulting Lois as stupid for not seeing past them outsold the FANTASTIC FOUR that began the Galactus trilogy when they went on sale the same day, much as we’d all agree the esthetic worth of the two stacks in the reverse order. But the Marvel titles were gaining in sales efficiency–the percentage of copies printed and shipped out that actually sold. That was a critical factor in profitability, and the best measure of immediate response to the appeal of the comic. Given the belief in the covers’ importance, deciding to have a single visual hand on DC’s covers and placing that responsibility in Carmine was a weighty decision.

It was a few years later when I began spending time at DC and with Carmine, and another few before I was present when he designed covers, so I’m not sure when he evolved his practices. But by the early ’70s, he had a very fixed ritual: an editor would bring the completed artwork for an issue in to Carmine’s office, he’d thumb through the boards (maybe reading a bit, maybe not) looking for the critical visuals or elements. There might be some back and forth with the editor, and then Carmine would pick up his chosen tools: a ballpoint pen and a piece of bond typing paper.

Two idiosyncrasies here: typing paper is not in the same proportion as a comic book, so any sketch done on it is likely to require some adjustment to fit those proportions. And after decades of using an artist’s pencil (and on occasion, pen or brush), Carmine was chasing to use a very different tool. My personal interpretation of this is that he wanted to be an executive, and so he used the tools of an executive even though he was stepping into an artist’s role again for the moment. He had disposed of his drawing board and art files, and whether it was a matter of self-image or how he wanted to be seen, I believe that was his unconscious motive.

The sketches that emerged from this process were raw design dynamics, occasionally with some emphasis on expressions when the faces were large enough images, but principally defining the poses, ideas and negative space. Many were inspired, many were powerful. And when you’re called upon to do a dozen in a week, some based on issues that had very limited visual imagery, the duds can easily be forgiven.

Sometimes no cover emerged: when Gerry Conway brought the boards for the first version of SECRET SOCIETY OF SUPER-VILLAINS in to Carmine, the pages were flipped, the absence of a headquarters for the villains noted, and the whole issue sent back for a redo. Or other changes could be required: my first Aquaman story was sent back for another, better writer (David Michelinie) to redialogue after Carmine reviewed it in the cover conference.

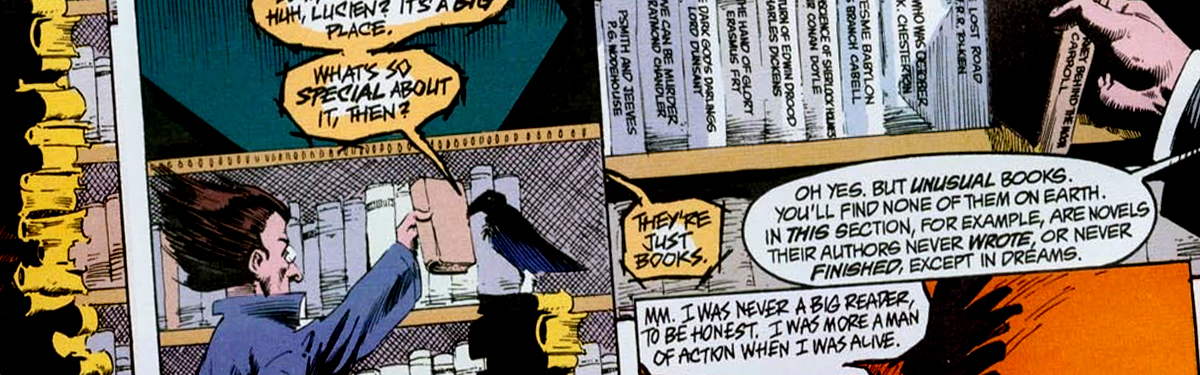

Artist editors (of whom DC had several in those years) might have picked up a pencil and offered dueling ideas occasionally, or more often took Carmine’s sketches and drew over them, preserving the dynamic and adding detail and expression. I watched Joe Orlando do that many, many times, to great effect. And there were times when editors brought in a finished piece of art they’d been offered as a potential cover for approval; I watched that happen with Wrightson and Kaluta pieces, and I’m sure there others.

And there were artists who were regularly in the office who were invited into those meetings, most often the principal cover artists of a period; Neal Adams, Nick Cardy, others. (Joe Kubert was, of course, both editor and cover artist on his titles; I never got to watch him and Carmine work up a cover but it must have been a joy to see.). And when the artist returned with the cover, it was brought into Carmine for inspection and approval.

I don’t know what happened with that JLA cover, but I can imagine Carmine looking at Gil’s version, wagging his cigar in disappointment, and asking Neal to come in from his workspace a few offices away to fix it. Neal might have even volunteered to do a new version. And I’d lay a side bet that editor Julie Schwartz would have been silently shaking his head, unconvinced that it made a damn bit of difference. And, of course, no one knows whether it did.