When Taschen decided not to do ahead with the last two volumes of the expansion of the ’75 YEARS OF DC COMICS’ book, I had already completed the interviews to go in front of the books. They’ve been generous and are allowing me to post them here. First up, a conversation with the woman who is one of my two most important mentors, a dear friend, and a vastly underrated force for the creative growth of comics at a time when it was an unlikely path.

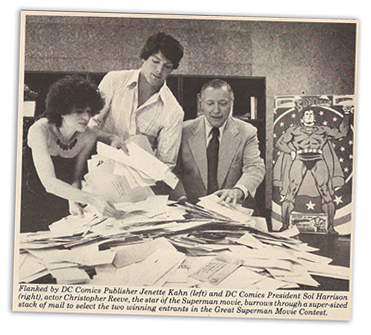

INTERVIEW WITH JENETTE KAHN

INTERVIEW WITH JENETTE KAHN

June 8, 2012

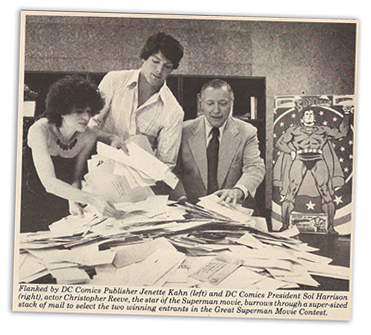

Jenette Kahn arrived at National Periodical Publications in 1976 as a 28 year old Publisher from outside the comics field, promptly changed the company’s name to DC Comics, and over the next 26 years led DC in inimitable style and shook the comics world again and again. From changing the economic models for comics’ talent, to breaking creative boundaries championing projects like THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS, many of the causes of DC’s successes in the Dark Age could be traced back very personally to her office and her convictions.

She came to DC with a background in children’s magazines, which is how DC’s corporate owners thought of their business…but she was also a serial entrepreneur, and passionate about fine art, with friends like Andy Warhol, whose prints graced her office. The executives who hired her wanted to change DC, but could hardly have predicted the paths she took, which led her from opening DC’s doors to the British Invasion of talent, to bouncing through the mine fields of Angola in an armored half-track creating a project that would be honored at the White House.

An energetic and distinctive spokesperson for the company and the comics medium, she brought national attention to projects for the public interest, like the creation of a Wonder Woman Foundation honoring grass-roots women activists, and projects to keep the DC heroes vital and successful, including the phenomena of the 1986 reboot of SUPERMAN (a radical step at the time) or his death in 1992. Whether crusading for diversity in comics, or simply step-by-step refusing to accept their time-honored limitations, she brought her own agenda to the field.

Since leaving DC in 2002, she has gone on to be a film producer, building on her long experience working on some of DC’s most successful films to do her own projects, including the acclaimed GRAN TORINO.

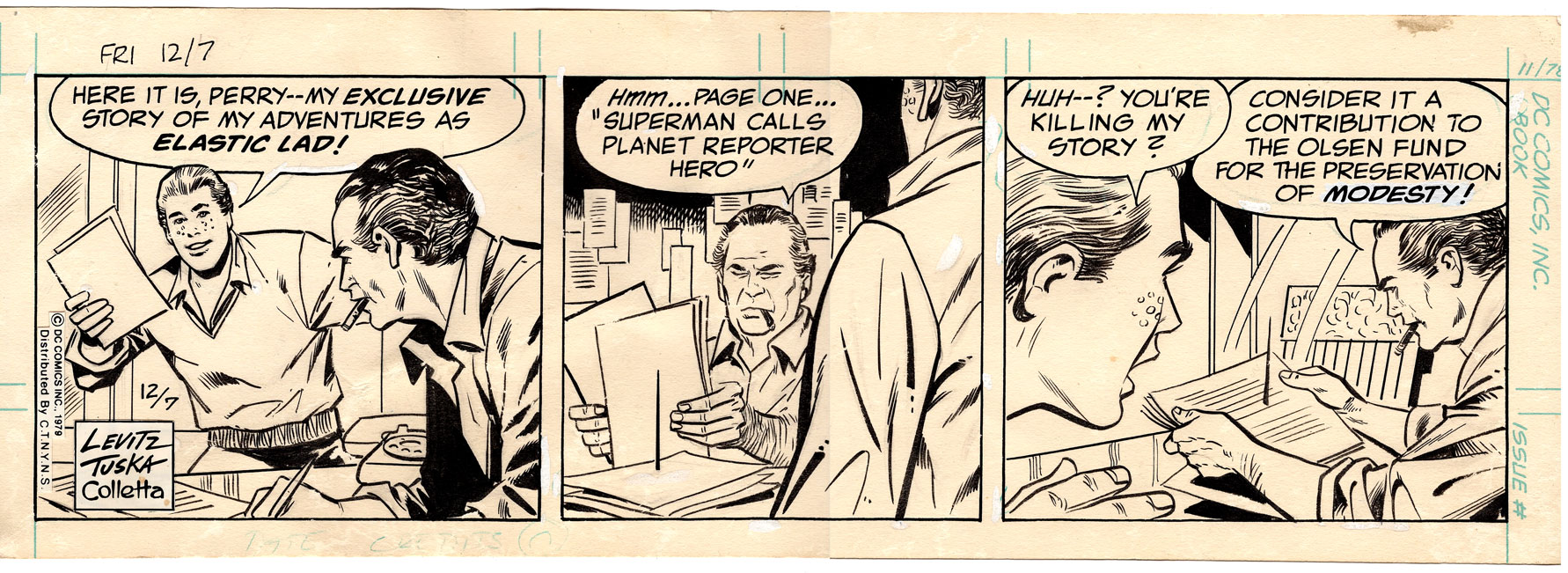

Interviewing her at the Warner Bros. offices in June, Paul Levitz flashed back to so many hours they’d spent across desks there, working, planning and laughing. And as they talked, remembering the extraordinary selection of original artwork that had been on her walls, or even selected as her furniture. Journey back with two old friends, reminiscing:

Batman or Superman, and why?

My favorite character of the two, without question, is Batman. I felt so strongly about him even when I was a little girl. The reason, I think, even then, was he made himself a super-hero. He had no special powers; didn’t come from an alien planet; but worked to become the world’s best detective, to become the best athlete. It made me feel that human potential, and hopefully my own, was unlimited.

As I grew older, I also noticed that there was a serious neurotic side to Batman, and I saw him as an artist as well, and that too just upped the ante for me with Batman.

Art or commerce?

Hmmm…are we saying do I prefer art or commerce, or are comics art or commerce?

This is just a question: art or commerce. It’s a rorschach question.

Comics at their best are art, but we at DC published more than our share of mediocre comics, and I would never deign to call them, or dare to call them art. But hopefully even if they were mediocre they sold. At their very best I really see comics as art and the medium itself as an art form. Like the movie business, though, it is the comic book business, and the business part has to be paid some deference to. Nothing is better than the collision of comic art at its highest, and a truly responsive audience that supports it.

Now let’s go back to Groundhog’s Day, 1976, when you arrived at DC. How weird was it to parachute into the middle of a group of people who’d worked together for years, arriving as the first outsider to arrive with authority in ages?

Now let’s go back to Groundhog’s Day, 1976, when you arrived at DC. How weird was it to parachute into the middle of a group of people who’d worked together for years, arriving as the first outsider to arrive with authority in ages?

It was challenging to come to DC and to be younger than almost everyone on staff, and to be an outsider, and to be a woman. Although he has since denied it, Joe Orlando was always said have been throwing up in the men’s room when he heard I was hired. Joe, of course, to become one of my most favorite people to work with; a wonderful editor and person.

But, I think, what made me think that things would work out ultimately was that I loved the medium, I loved comics. I didn’t just come in as an executive thinking, “Oh, it’s a business, I’ll run a business.” I loved the medium itself—the heartbeat of DC Comics, and everyone else who was working at DC felt the same way. I thought we could bond eventually, although it would take time, over that.

No frogs in the sheets or hazing?

I was lucky, no one sabotaged me…at least not in a way that I noticed.

Were there Jenette Kahn imitations behind my back? I’m sure there were many.

That’s a grand tradition in the company. I walked the halls once and passed Bob Schreck doing an imitation of me, and he was utterly mortified as I was applauding.

That’s a grand tradition in the company. I walked the halls once and passed Bob Schreck doing an imitation of me, and he was utterly mortified as I was applauding.

But you know at MAD it was a form of respect. I always said, when I took over MAD in the wake of Bill Gaines’ death that I hadn’t been accepted because I hadn’t been parodied in the pages of MAD. It wasn’t until drawings of me began showing up in MAD that I realized I finally, finally had made it.

When did you start feeling like you were accepted at DC? What started to change?

I think it began when I formed very strong alliances with you and Joe. We said comics have so much potential, and if we work together, shoulder to shoulder, we can change the world a little bit. That was the initial foundation, and over time more people joined us on the Long March Through China, but that small core group would stay late, talk about all the things we wanted to do with comics, how they could be. And almost every one came to pass.

It’s amazing how much of the stuff we worked in became part of the texture of what the medium is today.

It’s so gratifying. We had passion, we had vision and we had a will to make things happen.

When I look at your accomplishments it’s a long and weighty list: giving people an economic stake in their work for the first time in mainstream comics, breaking the boundaries of what could be done with established properties with projects like THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS, advocating the role of design in comics, making comics’ oldest publisher its most innovative, and leading pro-social projects like the landmine comics or SEDUCTION OF THE GUN. Can you rank them, and is there one that’s important to you that I didn’t put on the list?

That’s a tough question. I did want us to be an innovator, but I wanted just as much that our creative talent got the rights that they deserved, and that they would have a financial stake in their creations. It’s the economic side and the artistic side, and they had to go, somehow, in lockstep together.

I think that’s a good representation of your passions, and I think, ultimately, the creative successes wouldn’t have happened without the economic changes.

I do believe that’s true. I don’t think we start to see a second Golden Age in comics—or an Elizabethan Age—such fecund creativity without first making our creative talent believe they were stakeholders.

You’ve always surrounded yourself with art, from Warhol and the great photographers to your eclectically designed homes, and with comic art from George Herriman and Lyman Young and Jeff Jones. If you could have any one piece of art from your time at DC, what would it be?

You’ve always surrounded yourself with art, from Warhol and the great photographers to your eclectically designed homes, and with comic art from George Herriman and Lyman Young and Jeff Jones. If you could have any one piece of art from your time at DC, what would it be?

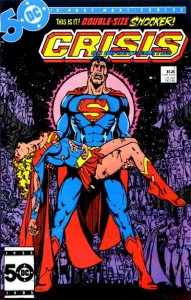

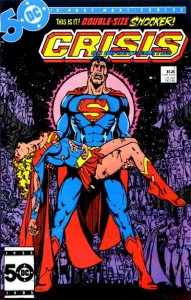

Hmm…I’m seeing covers in my head. Maybe George Perez’s cover from CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS, with Superman holding Supergirl’s body and howling to the heavens

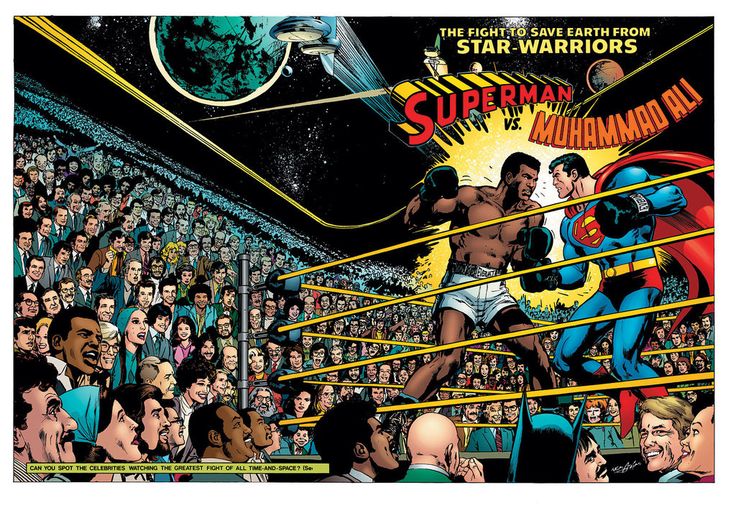

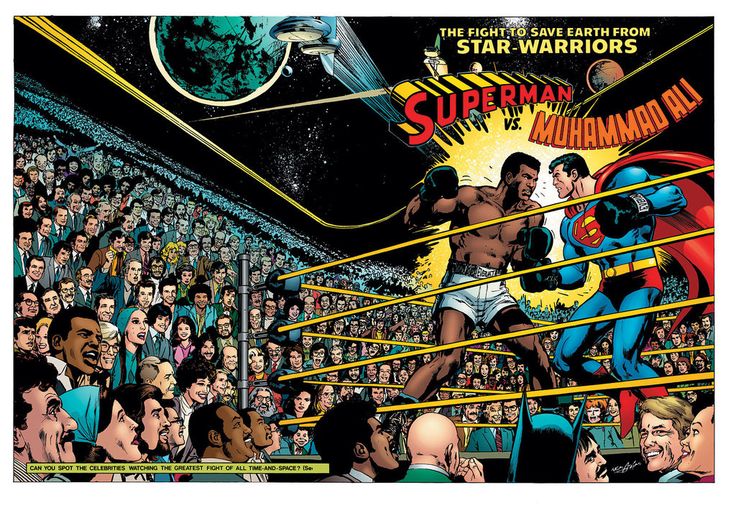

I was betting you’d come up SUPERMAN VS. MUHAMMADALI—more hours working on that cover.

Without question. I have a lot of affection and investment in the SUPERMAN VS. MUHAMMAD ALI cover, but it was a one-off. (Jenette had personally spearheaded that project, including the enormous task of getting consent from literally hundreds of celebrities and comics people to being incorporated in the cover.) CRISIS signified that we were willing to take our traditional characters and were willing to truly push the envelope. We had decided that when things happened in the DC Universe, and when they happened they would have real consequences. If you had a death, the death would be real. People would mourn that death. I think that cover signaled what we were going to do, and we were true to it.

Your office at DC was a salon of remarkable people, many from far outside comics. Can you pick two or three who you connected to comics over the years?

Your office at DC was a salon of remarkable people, many from far outside comics. Can you pick two or three who you connected to comics over the years?

Senator Patrick Leahy—it turned out he was a BATMAN fan, or at least he was a self-professed BATMAN fan. He mentioned that at a dinner Time Warner held for him, and that became a relationship based mainly on BATMAN formed from that public profession.

Perhaps Judy Collins, the singer/songwriter. She is an Ambassador for UNICEF and someone I knew from outside comics. When she asked me what could be done for kids who were affected by landmines, I thought we could publish comics that would warn children of the dangers of landmines. Actually, we proceeded to do just that.

Who were some of the unlikely people you were thinking of?

Some of the others who were in your office seemed unusual, but I don’t know that the connection to comics was as clear. Jaron Lanier, Tom Wolfe…

Some of the others who were in your office seemed unusual, but I don’t know that the connection to comics was as clear. Jaron Lanier, Tom Wolfe…

Jaron Lanier, who invented virtual reality, that incredible writer Tom Wolfe, hip hop spokesperson and architect, Fab Five Freddie, Ice-T…I guess it was a motley crew.

You’re responsible for creating successes in children’s magazines with KIDS, DYNAMITE, SMASH; in books, with your own IN YOUR SPACE; in film as a producer, with GRAN TORINO; and, of course, comics. Other areas that you’ve been more quietly involved in for years, like Harlem Spaces or Exit Art. But you gave comics the greater part of your career. What was the magic that kept you there?

I loved the medium, I loved the characters, I loved the creative process. Actually, I also loved the people I worked with at DC, and that was critical. We had a warm, collegial atmosphere—it was a great place to come to work.

I think it was also that we were building something; that we were dedicated to change, making comics a sophisticated art form, developing our characters, empowering our talent. Change takes place slowly, and it took many years to implement the things that we envisioned early on. The ability to do that, and to continue to grow, and to continue to push the envelope; that’s really what engaged me for so many years.

Your office at DC was a salon of remarkable people, many from far outside comics. Can you pick two or three who you connected to comics over the years?

Your office at DC was a salon of remarkable people, many from far outside comics. Can you pick two or three who you connected to comics over the years?