I always was fond of the mail. Goes back at least to when the subscription copies of ACTION COMICS would arrive (from the $1 sub I talked my mom into letting me order from ACTION #300 when my babysitter brought it for me). I gave up the subscriptions after my dog arrived in my life; Chee-Chee despised the mailman, and as a point of honor would grab the mail as it came in through the slot in the front door, and toss it around. Comics with bite marks are even less mint than the mailing fold down the middle caused.

The years when I published fanzines confirmed my pavlovian reaction to the mail. Every day some new orders for The Comic Reader might arrive, or perhaps a new article or column I could publish (no email attachments to open in those days, or PayPal credits). As the circulation grew towards its final tally of 3,500, the daily take grew commensurately.

Then there was the mail that came into DC for the letters pages I was responsible for putting together and answering. All in, I did over a thousand text pages for the company, from Phantom Stranger #25 onward. I think it’s the largest number of texts anyone’s contributed to comics, but since the vast majority of such work is uncredited, that’s a biased and unsupported claim. Love to hear from anyone with a contrary claimant, however.

Those letters ranged from the youngest kids’ scrawls for the mystery comics, to long and complex analysis from serious fans of the Legion of Super-Heroes. There was a physics expert pointing out my errors in depicting a black hole, and lengthy, thoughtful literary discussions from a Tulane grad student who would become a professor there and a lifelong friend. Oh yeah, and there was the letter from Harlan Ellison to Swamp Thing that he was so pissed I printed. Sorry again, Harlan.

And when I got to the publisher’s desk at DC, some of the best mail were the thank you notes from creators whose work I had rejoiced in, either in appreciation of a payment the company made, or of something I’d thought to send. I’m smiling, recalling warm words from early Superman and Starman artist Jack Burnley for a reprint payment, and a beautifully drawn self-portrait of Jack Davis, for something MAD-related, of course.

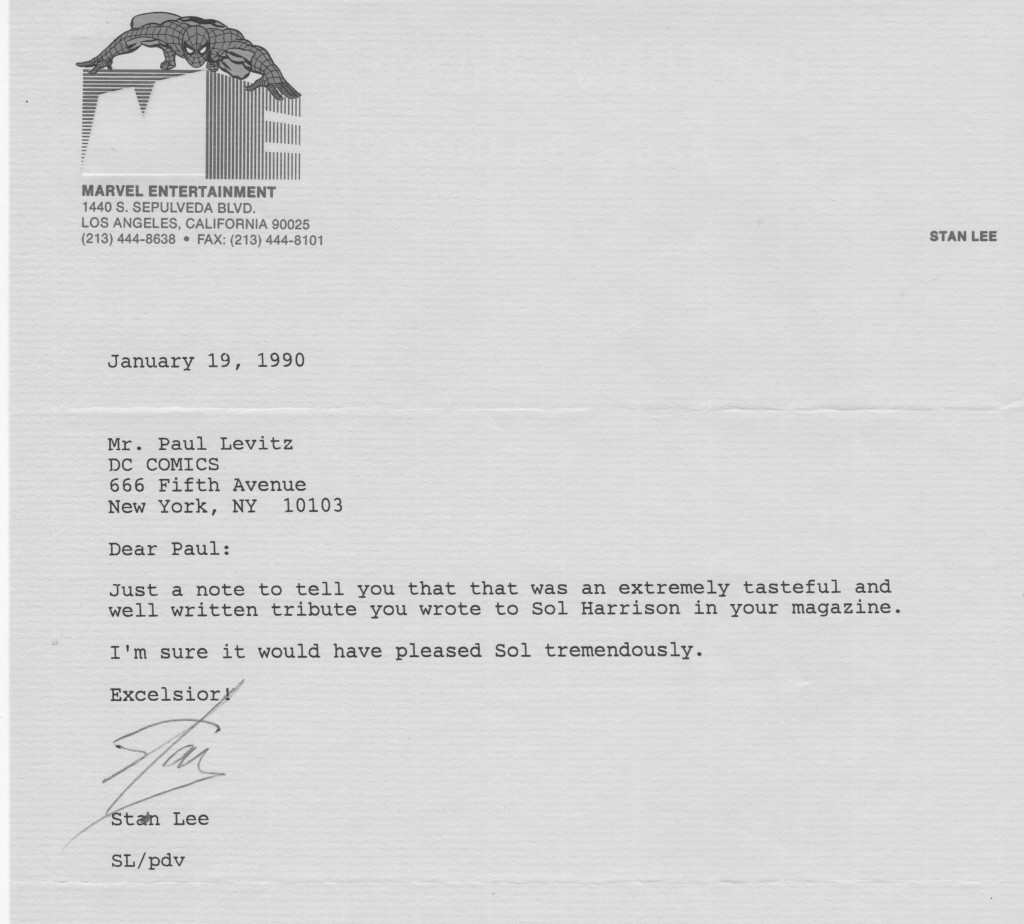

But my absolute favorite fan letter is this one:

I didn’t really know Stan at that point in my career. Perhaps we’d shake hands once or twice, but there was no reason for me to believe he knew I existed (I have trouble remembering people I’ve casually met, and even in those pre-cameo days, Stan was a celebrity who’d encountered countless folks). And he’d taken the time to read the obit I’d written for former DC executive Sol Harrison, liked it, and gone to the trouble of sending me this note.

Stan Lee liked a “bullpen” page I wrote. ‘Nuff said.

Next time, let me tell you about a letter from Alan Moore…